On the Nepali Language and Unicode

The Nepali language gets very little representation on the internet. Take, for example, the Nepali Wikipedia which has about 33 thousand articles. The Esperanto Wikipedia boasts 8 times that number (at around two hundred thousand articles), which is kind of sad, because Esperanto is an artificial language created by one person in the 19th century. It is spoken by a meager 2 million people worldwide. Compare this to the Nepali language, which has more than 25 million speakers.

It's as they say, “whoever controls the media controls the mind”. And the media of the 21st century, the internet, is so desperately out of Nepali's hands that, not only do we read the news, articles, the weather, and novels in English, but we go on to caption our photos of warm, intimate moments in English. Our pop culture is stuffed full of references to Hindi media. My little brother, who is not even 10, will sniff my phone from a mile away and hide out in some corner to watch Motu Patlu on YouTube. He might not be as fluent in Hindi as he is in Nepali. But in his little world, Hindi is the language that superheroes speak. And Nepali? Only his annoying brother.

I'm not saying that I'm any better. If anything, I'm far worse. I'm one of those people who, after being told a phone number, says, "Okay, repeat that. But in English". Ask me to translate this very post to Nepali and watch how fast I run away. My friends are, frankly, no better.

The problems are much worse for other languages of Nepal. The Newari Language is listed by UNESCO as being “definitely endangered”. The Kusunda language has speakers in single digit numbers, which is particularly unfortunate because Kusunda happens to be a language isolate, so once it’s gone, we’ll lose any chance of accurately reconstructing it. Half of the 123 languages of Nepal are endangered.

In this post, I will talk about Unicode for Nepali language in hopes that I can shed some technical light on Unicode in Nepali context for the uninitiated. The idea is to let interested people know of the tools and ideas in Unicode, specially in context of the Nepali language to encourage adoption and usage.

Some background

Note: The numbers starting with ‘0x’ and 'U+' are Hexadecimal numbers. 'U+' prefix additionally implies that the number following it is a Unicode code point.

Computers fundamentally think in numbers. To a computer, a picture is a 2d matrix of color intensity at each pixel as recorded by the camera. An audio recording is, similarly, a sequence of amplitudes of a sound wave recorded several thousand times each second. It goes without saying that text is also read by the computer as a sequence of numbers.

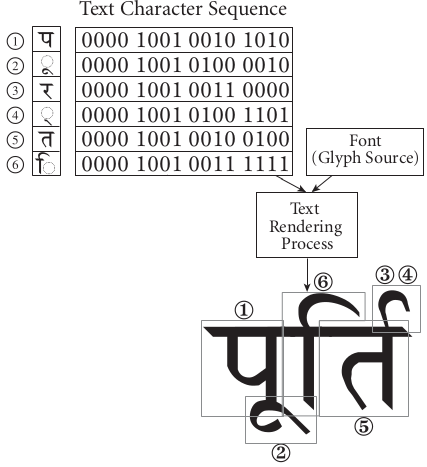

Of course, what the numbers mean to the computer is entirely dependent on the program that reads the data. In case of a picture, the numbers are used to vary the brightness of color elements on the monitor. For an audio, the data sequence is used to proportionally adjust the voltage across the speaker coil, which causes the membrane to vibrate and create sound. For text, these numbers will be used to do a wide variety of task. If you’re typing, numbers corresponding to the alphabets you press will be stored in the memory. These numbers will be used to look up characters inside the font file, which stores a visual glyph for each displayable number. That will be drawn on the screen (after many more steps).

So, it seems that for the computer system to support text at all, characters will have to have a standardized mapping to numbers. If the font file and the keyboard don’t agree on what the number 65 is, then the wrong character will be displayed on the monitor.

ASCII is the standard mapping of these numbers to characters. It assigns the numbers from 0 to 127 to English alphabets and symbols. Because the early development of computers was centralized in the US and UK, ascii encoding became the primary method of text representation on computers.

Computers almost universally store data in blocks of 8 bits (a byte) which can represent 256 numbers (28). ASCII only uses half of that (128 characters). So, with ASCII, half of the representational space of a byte goes unused. There have been several extensions to ASCII which make use of the unused space from 128 to 255.

So how do you type Nepali in ASCII? Well, you don't. ASCII is, by its very definition, American. In the early ‘90s, Bureau of Indian Standards came up with its very own encoding scheme called ISCII. ISCII is an extension of ASCII, so it retains all characters from ASCII in their rightful place. From 128 to 255, it stores characters used in the languages of India. Interestingly, ISCII actually unified a bunch of similar scripts like Devanagari, Tamil, Bengali, and Oriya. So, a number 164 (0xA4) in ISCII can mean all of the following: अ, அ, অ, ଅ and more. The idea was that, since all these scripts are descendants of the same Brahmi script, they behave similarly and represent similar sounds, which is true, so all four of the above letters represent the same /ʌ/ sound.

To switch between scripts in ISCII, you just change the fonts rendering the numbers. If a Devanagari font is selected, computer displays Devanagari characters. If a Tamil font was selected, it displays the same text in Tamil. The equivalent for English language would be to do assign numbers to the 26 English alphabets, and switch cases by changing fonts. The phonetic information stays the same but the representing characters seem different. ISCII used a special ATR byte to specify which script the fragment of text was in. ISCII is important historically, because Unicode specification for Devanagari and other Indic scripts is based almost entirely on ISCII. The ATR byte was not adopted by Unicode because font attributes are not a part of Unicode.

In Nepal, however, the government didn't initiate any efforts. What I think happened instead was that people or groups (like Muni Shakya) independently assigned the 256 numbers to various characters and ligatures. Which character a specific number represented was completely up to the font you chose. That must have been messy. Fonts are meant to change how the text looks, not what it represents!

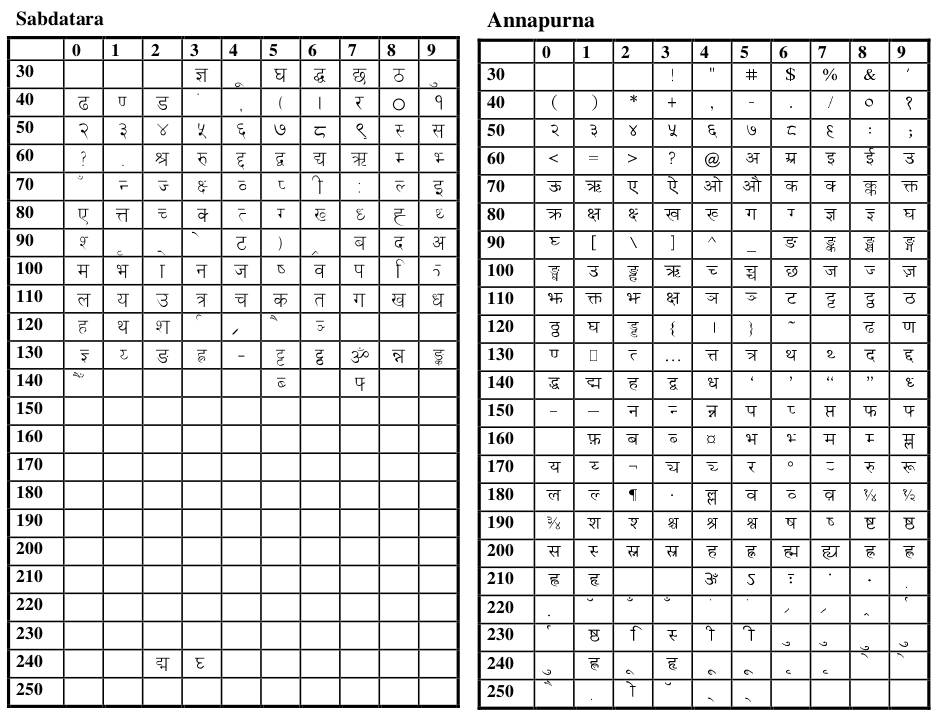

The table below shows the character mapping of two Nepali fonts from the late ‘90s. You’ll notice how same field of the tables doesn’t encode the same character. Both learning to type in these fonts and changing the fonts must have been an inconvenience.

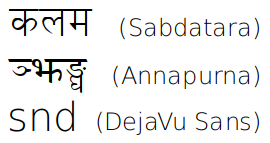

So far, I have talked exclusively about the representation of text. Typing was a different beast entirely. Suppose that you were using the Annapurna font. Since keyboards come in the standard QWERTY layout, if you pressed the A key (which is internally ASCII 65), an अ would appear. But on changing the font to Sabdatara and it would change to a द्ब. The image below demonstrates how, typing कलम in Sabdatara font, and then changing it to Annapurna results in garbage.

But thankfully, over time these mappings stabilized to the what is now known as the Traditional or Remington's keyboard layout. Generally, if someone over 30 tells you that they can type in Nepali, what they probably mean is that they can type in the traditional keyboard layout. It is what you type if you use the Sagarmatha or the Preeti font.

Unicode

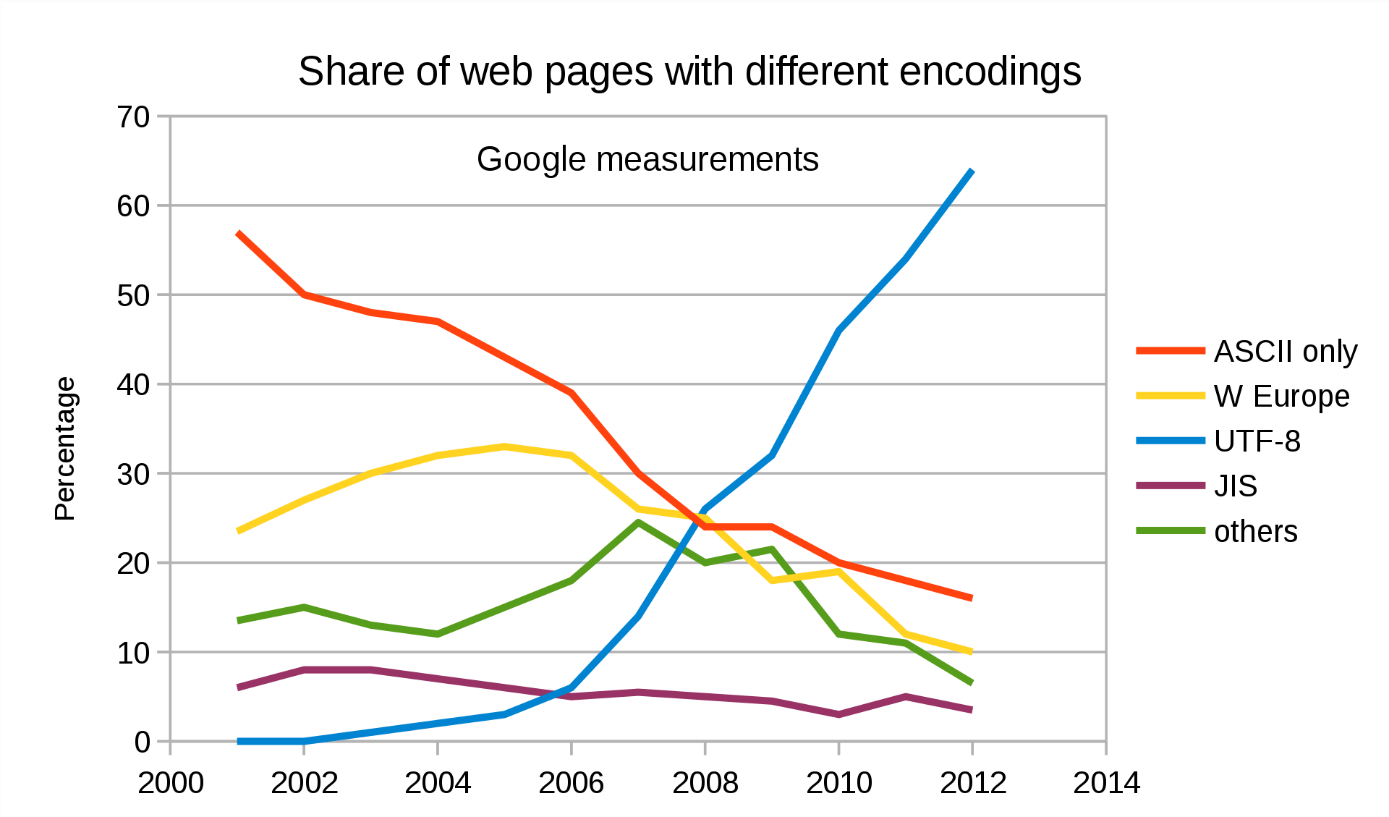

Naturally, India was not alone in wanting an encoding for its scripts. The late ‘80s and the ‘90s saw the rise of encoding schemes such as PASCII, VSCII, JIS X, many ISO standards, and much more, each developed by a particular country or a group of countries to encode their language. All this was fine and dandy for the systems back then. But then came the Internet.

The Internet pretty much broke everything. Computers all over the world were expected to understand each other, but they spoke in different encodings. If you didn’t encode your data in the same format as the receiving computer was set to, your text would render as garbage. The problem was that a number in one computer in one country represented something entirely different in another computer in another country.

Unicode was designed from the ground up to support all scripts of the world. It currently has 1,37,994 characters from 150 writing scripts. Unicode puts each character its own unique identifying number. For example, the number 2325 (U+0915) uniquely identifies the Devanagari letter क, the number 70658 (U+11402) identifies the Newari letter 𑐂, the number 65 (0x41) represents the English capital letter A and the number 24859 (0x611b) the unified Chinese, Japanese and Korean ideograph 愛. These numbers mean the same thing no matter where in the world you are or what computer you are using. These numbers are also immutable, meaning that, Unicode won’t ever change what a number means, hence maintaining backward compatibility.

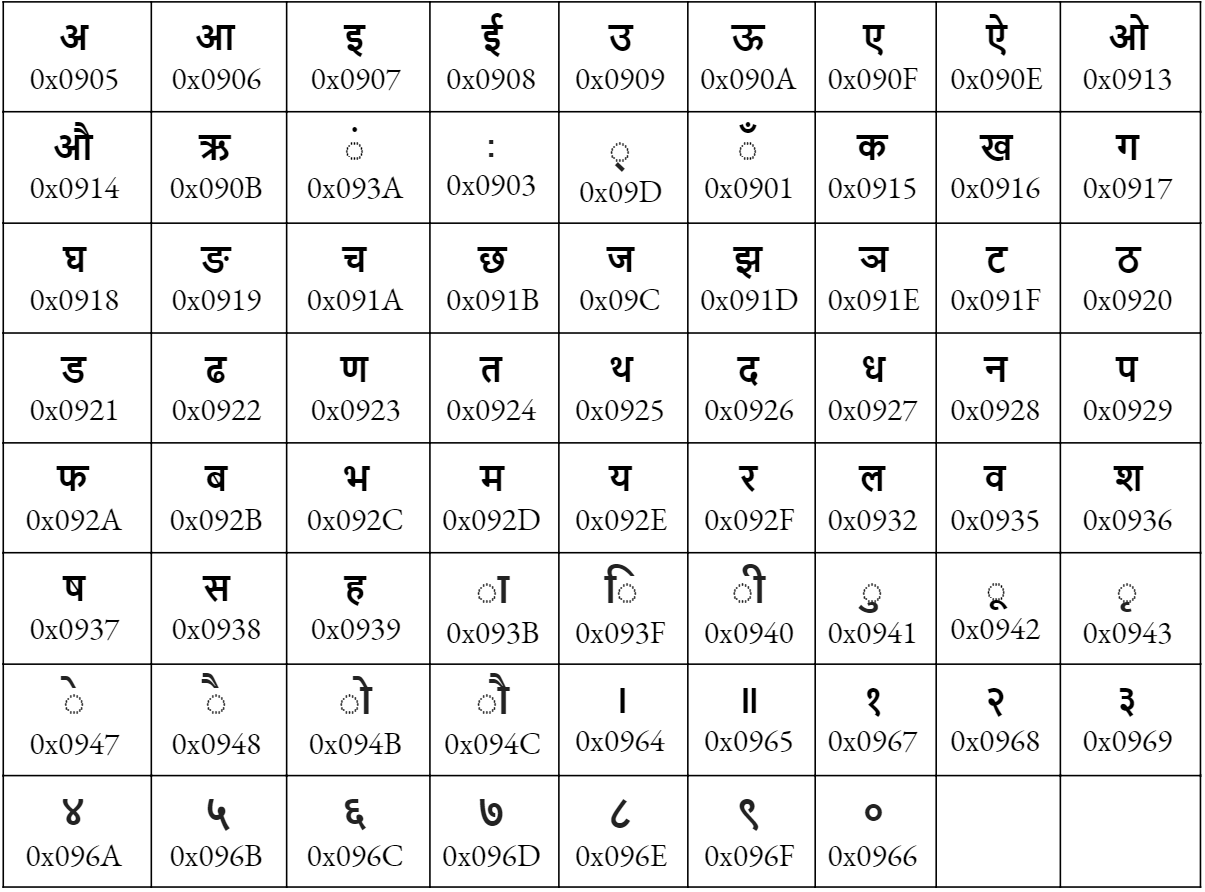

This table lists all

Nepali Characters in the Unicode Devanagari block with their codepoint numbers.

This table lists all

Nepali Characters in the Unicode Devanagari block with their codepoint numbers.

Characters of the same script live in the same block. A block is essentially a range of numbers. For example, Devanagari characters live in the U+0900 to U+097F block. Newa is in the U+1900 to U+194F block. The Limbu writing system, Sirijanga Script, lives in U+1900 to U+194F block.

The advantage of separating language into blocks, is that each block can get its own kind of treatment from the software. We know that different scripts behave differently. In Devanagari, some characters go above the previous character, some under. Some change the character itself. In Tibetan, diacritics stack up vertically. A single Urdu character, when typed, can change how the entire word looks. Not to mention that scripts have different directions of reading. Chinese is written from top to bottom. Urdu is written from right to left. All these quirks can be handled by software based on what block the characters come from.

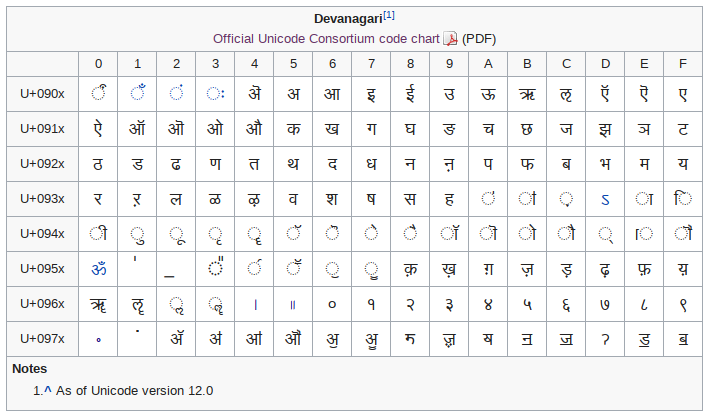

The Devanagari block is shown below. It was taken from Wikipedia.

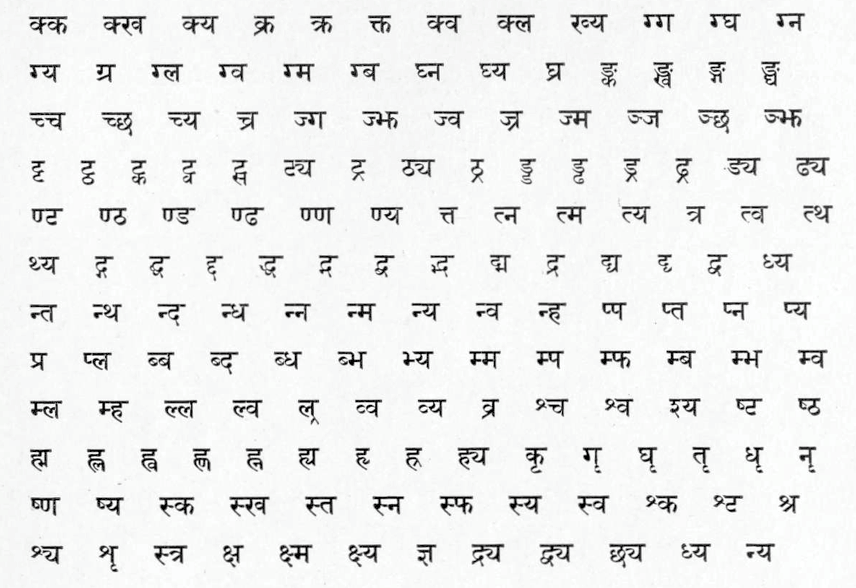

Now, if you look at the table above, you will notice a lot of characters missing. Where is क्ष? Or द्य? Or all the half forms like क् , ग् , and the rest? Well, because Unicode was based on ISCII, and since Hindi considers क्ष, त्र and ज्ञ to be compound characters, they aren’t allocated separate code points. That doesn’t mean you cannot type it, though. You just have to input the constituent characters and the text-rendering system will take care of the rest. क्ष makes क��्ष, त्र makes त्र and ज्ञ makes ज्ञ automatically.

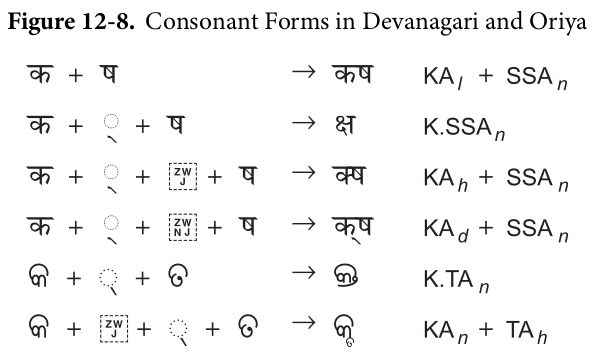

Unicode Specification on how a software should handle compound characters in Indic scripts.

So then, what if you want to type out क्ष explicitly? Unicode provides a character called Zero Width Non-Joiner (ZWNJ) (zero width because it doesn’t take up any space in the text). But it prevents the Halant ् from changing characters to their half forms. Similarly, there is a Zero Width Joiner which explicitly asks for the half form to be displayed, even if there isn’t a character next to it.

Now, if you look at the table for Sabdatara and Annapurna font above, you’ll notice that the half forms are explicitly encoded. That is probably an artifact from the printing press era. When typesetting for the printing press, or when using a Linotype, a क followed by a ् wouldn’t magically change into क्. You would have to select the correct type blocks manually. That kind of thinking could have carried over into the font design process.

But computers are smarter than that. They will easily substitute the glyphs for you. The only thing to keep in mind is to use your ZWJs and the ZWNJs when you want the other forms.

Unicode intends to depict the underlying characters rather than the renderings. Think of it this way: प्राप्त is the rendering and प + ् + र + ा + प + ् + त is its underlying character composition. Unicode delegates the rendering to the display system. This model of text encoding is called the Virama-based model (virama meaning halanta), and is not unique to Devanagari.

The Unicode 12.0 specification has an insightful image to clarify further.

UTF

Unicode is mostly concerned with assigning abstract numbers to characters, and describing their properties. Unicode Transformation Format, or UTF is the implementation of the Unicode specification. UTFs are the algorithms which convert these abstract numbers into bits and bytes that are eventually stored in the memory, processed or transmitted.

Only three Unicode Transformation Formats are in widespread use: UTF-8, UTF-16 and UTF-32. The numbers in their name signify the number of bits they use. So UTF-8 uses 8 bits (one byte), UTF-16 uses 2 bytes and UTF-32 uses 4 bytes. The figure below will try to demonstrate how UTF8 works. It’s okay if it ends up confusing you instead. Unless you are writing multilingual computer programs, it is not generally necessary to know how these encoding schemes work. Just remember that most all of internet uses utf-8 because it is the most efficient encoding.

Nepali Input

Unless you can already type in the traditional layout, I recommend that you try out the Phonetic layout by Nepali Language Technology Kendra. I’m sure any reasonably dedicated person can learn this layout in a day.

As it turns out, it is a fairly simple exercise to create a new keyboard layout from scratch. I was able to make myself a modified version of the Phonetic layout in less than an hour. To make your own layout, download and install the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator tool.

Nepal Language Technology Kendra website also provides keyboard layouts for Nepali Keyboard layouts for Linux. On Android phones, you can install either Hamro Keyboard or Google Indic keyboard, both of which are excellent. On iPhones and iMac, simply activating the required input method in Settings should suffice.

Fonts

Google Fonts has a usable selection of fonts for Devanagari. To filter the fonts by the language, find the Language dropdown and select Devanagari (even though it isn’t a language).

Featured photo of Linotype by werner moser from FreeImages.com